Intel Core i7-3770K Review

Manufacturer: IntelUK price (as reviewed): Around £240 inc VAT

US price (as reviewed): Around $310 ex tax

It feels as though Intel’s Ivy Bridge CPU launch has been death by 1000 delays. Following the huge success of its Sandy Bridge architecture last January, and the uncompetitive response from AMD in the form of its Bulldozer architecture CPUs, Intel has had the luxury of being able to wait, pushing back the release date to ensure production and clear the Sandy Bridge inventory. Comically, this has meant that motherboards based on the new 7-series chipsets accompanying Ivy bridge's launch have been on sale for over a month, something we can’t imagine motherboard partners have been too happy about.

Finally though, the teasing is over and we’ve gotten our hands on Intel’s latest. The Intel Core i7-3770K is the new top-end part in what Intel sees as its mid-range, replacing the Core i7-2600K/2700K. It’s a 77W quad-core chip with hyper-threading, running at a nominal frequency of 3.5GHz, but turbo boosting up to 3.9GHz. Directly replacing the Core i7-2600K in Intel’s product lineup, the Core i7-3770K should go on sale today for the same price of around £240.

click to enlarge

All about Ivy Bridge

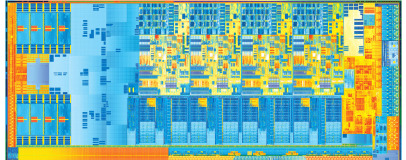

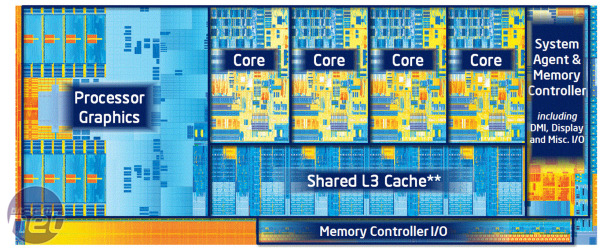

As a ‘tick’ to the Sandy Bridge architecture’s ‘tock’ the new Ivy Bridge CPUs are more of an incremental upgrade than a total overhaul. However, there are some significant improvements right through the CPU, most notable of which are the switch to a 22nm production process and the introduction tri-gate transistors. You can read our 'All About Ivy Bridge' article here for a more detailed explanation of tri-gate transistors, but the end result of both of these technologies is a smaller die, with more transistors, that requires less power. These two technologies see Ivy Bridge CPUs deliver an 18 per cent reduction in TDP in comparison to Sandy Bridge, despite near identical clock speeds.While the CPU architecture itself is unchanged, Intel has made improvements when it comes to Instructions per clock (IPC), optimising the CPU’s core, level 3 cache and memory controller as well as adding a few new SSE instructions. There’s also been a change to the way the CPU handles sleeping and awake cores, dubbed Power Aware Interrupt Routing (PAIR) to improve the ability to prioritise and wake inactive cores.

While there have been relatively minor changes to the CPU component of the chip, Intel also claims to have made significant improvements to Ivy Bridge’s integrated graphics processor (IGP). The Intel HD graphics 4000 found in both the Core i7-3770K and the Core i5-3570K sees the execution unit (EU) count rise from 12 in Intel HD 3000 to 16, as well as support for, at last, DirectX 11. Of course, no self-respecting PC enthusiast would want to run their system solely off of integrated graphics, but it’s a step in the right direct for mass-market users, and still brings the advantages of technologies such as Intel’s Quick Sync video, which benefit from the increased EU count. We'll be looking at Intel'd HD 4000 in a separate article soon.

Ivy Bridge Overclocking

Overclocking for Ivy Bridge is very similar to that of Sandy Bridge, but with the switch to 22nm it has arguably become even easier. As with Sandy Bridge, the use of a CPU with an unlocked multiplier, designated by the ‘K’ at the end of the CPU name, is essential, as the CPU’s ring bus still prevents any meaningful increases to the base clock.With lower stock power consumption though (the i7-3770K’s typical stock Vcore is around 1.05V under load), there’s more room for over-volting. Using a Corsair H100 liquid cooler, we’ve been able to use a Vcore of 1.4V without issue, although this has resulted in temperatures closing on the CPU’s TJ Max (maximum operating temperature before throttling) of 105°C. Motherboard improvements in the Z77 chipset mean that adjustments to the likes of the PLL or PCH voltage are now redundant, at least at an enthusiast level. With a decent quality motherboard all you should need to do is disable the Intel C-states (or adjust the CPU power levels up) and then increase the core voltage and multiplier.

However, those hoping for drastically higher frequencies in comparison to the Sandy Bridge will be disappointed, despite the CPU’s maximum multiplier rising to 63x. While much higher frequencies are now possible, you’ll need exotic cooling to reach them. We’ve found that the smaller production process and increased transistor count leads to hot-spotting on specific cores at higher frequencies. Three cores will be rock solid, but one will inevitably fail under load.

Our i7-3770K topped out at 4.8GHz (48x100, VCore 1.34V, Load Line Calibration = Extreme), reaching a peak delta T of 72°C in a 19°C ambient. Regardless of adjustments to the multiplier, base clock, core voltage or IGP, it simply would not remain stable at any higher speeds, despite CPU temperatures sitting comfortably 10°C below the TJ max.

However, we’ve also been able to test the i5-3570K, which was stable right up to 5GHz (50x100, Vcore 1.4V), so clearly there’s the usual degree of variation between CPUs when it comes to overclocking potential.

| Name | Nominal Frequency | Max Turbo Boost Frequency | Hyperthreading | TDP | Physical Cores | Level 3 Cache | Graphics |

| Intel Core i7 3770K | 3.5GHz | 3.9GHz | Yes | 77W | 4 | 8MB | Intel 4000 |

| Intel Core i5 3570K | 3.4GHz | 3.8GHz | No | 77W | 4 | 6MB | Intel 4000 |

| Intel Core i7 2600K | 3.4GHz | 3.8GHz | Yes | 95W | 4 | 8MB | Intel 3000 |

| Intel Core i5 2500K | 3.3GHz | 3.7GHz | No | 95W | 4 | 6MB | Intel 3000 |

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.